▲

Bells at Barrow Caistor Exhibition A Talk by Andrew King Clipper Yacht Race JHF exhibition Greenwich

▲

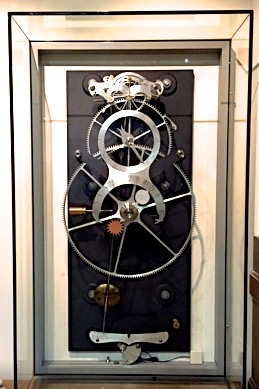

World record clock on display in the main gallery at Greenwich: Clock ‘B’

Royal Navy Commander Nick Chatwin OBE ‘emersed’ in the mechanism of Harrison’s ‘H1’ his first marine timekeeper and the only one to be built in Barrow-upon-Humber and tested on the Humber estuary, (1730-1735).

Commander Nick Chatwin, OBE with senior curator of Horology, National Maritime Museum, Rory McEvoy discuss the work of the ‘Master”. The portrait is a reproduction of the engraving by P.L.Tassaert after Thomas King’s painting of 1767.

On the wall: Harrison’s famous prediction for his ultimate pendulum clock: “… that it shall perform to a second in 100 days …"

Reflecting on Martin Burgess’ clock ‘B’ here still in its wax sealed acrylic case in the Observatory workshop;

its two year test confirms it to be the most accurate clock with a pendulum in free air ever made; vindicating Harrison’s forecast for his unique technology.

Beautiful precision! Clock ‘B’ now on public display in the main Gallery, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

In 1974 the renowned sculptural clock maker Martin Burgess was commissioned by Barclay’s Bank of Norwich to design and manufacture a sculptural clock for the city. Martin Burgess, a noted authority on the technology of John Harrison, (1693-1776) produced a remarkable sculptural interpretation of the very advanced high precision pendulum clock that Harrison made but did not quit complete before his death in 1776.

Harrison proposed that this clock, his ultimate statement in precise timekeeping, would perform to within three and a half seconds a year. This forecast based on his experience with the similar but less advanced pendulum clocks which he had made in the 1720s. One of these earlier clocks had been running in Harrison’s house at Red Lion Square, London to within twelve seconds in a year. Even the performance of these earlier pendulum clocks far surpassed anything available in the 18th. century, and not equalled, let alone alone exceed until the middle years of the following century; the forecast for Harrison’s ultimate clock was not equalled until the 1920s.

It is this ultimate design of clock with Harrison’s claim of accuracy which has bewitched, puzzled and of course doubted if not ridiculed which became a fascinating challenge. Martin seized the chance to meet this challenge as well as produce a monumental sculptural for the city of Norwich: a formidable prospect!

The original four year contract extended to twelve before Martin completed the work and this, because Harrison’s technology was a completely lost science. Harrison’s approach was directly in opposition to everything held sacrosanct by all other precision clock makers right up to the time of the invention of the Atomic clock in 1955. At the heart of Martin’s clock, is the final success revealing the truth of Harrison's claim for his technology.

Martin completed the fundamental working parts of a second clock; this partner to the Norwich clock remained with Martin until 2009 when it was acquired by Donald Saff, an authority in the world of fine art as well as a passionate follower of precision timekeeping.

The clock was taken to Frodshams of Sussex, specialist clock and watch makers who completed the work. The essential parts of the clock having been made by Martin, that is: the escapement, with the accompanying winding remontoir and the pendulum system. Martin had been able to run it to a reasonable rate but more adjustment was needed. All the dial work had yet to be made as well as the great wheel assembly although Martin had made the wheel itself.

This is the clock, clock ‘B’ now seen in the main Gallery of the Observatory of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, England. The clock was initially installed in the Observatory workshop where it was in public view; this is where all the final testing took place. In 2008 the clock was officially sealed with wax in an acrylic case; the sealing ceremony being fully witnessed. The only connection to the outer world was a link to a computer where the clock could be fully monitored. Here on the screen can be seen the rate of the clock, the arc of swing, the temperature, the barometric pressure and the humidity, all shown as graphs. All these factors are important but the final crucial hurdle, even though it represents a very small proportion of error, is the barometric pressure, as Harrison far more graphically called it: ‘the weight of the air’. On screen it was possible to see the varying pressure of the air and how the pendulum was reacting to it. At first the pendulum was acting as quite a good barometer, what was needed was to be able to cancel this error, exactly as Harrison himself described and this was finally achieved.

Over the following two and a half years the rate of the clock was represented by what appeared to be a straight line across the screen oblivious to all temperature and barometric changes. When this line was magnified it was possible to see peaks and troughs but as explained, these spikes were all but one thousandth part of a second. There is one more problem to be addressed and that is a small temperature error. During the heat of the summer the clock can lose two seconds but gradually returns to zero again; despite this, on average over the two and a half year period the overall rate was within one second, this rate well within Harrison’s forecast of three and a half seconds in a year..

No other clock with a pendulum in free air has ever performed at this rate.This is now recognized as a world record and as such a ceremony was held at the National Maritime Museum in 2014 where a representative of the Guinness Book of Records awarded the clock an appropriate certificate to commemorate the success.

In 2016 the clock was moved into the main Gallery where it can be seen alongside Harrison’s three sea clocks: ‘H1’ ‘H2’ and ‘H3’ and of course the famous Sea Watch, ‘H4’, Harrison’s masterpiece, the worlds first high precision watch and precursor of the later marine chronometer.

Whilst the technology of Harrison’s evolution of the marine timekeeper with the watch (‘H4’) led to the the precision wrist watch today, the equally revolutionary technology of his pendulum clock was lost when John Harrison died in 1776.

Andrew King, January 2017.